Who is Hoy?

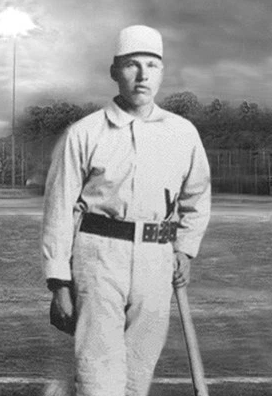

Dummy Hoy

William Ells worth “Dummy” Hoy (1862-1961) was the first deaf player to have a long career in the major leagues. He was born in 1862 in Houcktown, northern Ohio, graduated from Ohio School for the Deaf, began his professional career in 1886, played for several major-league teams from 1888 to 1902, and died in Cincinnati in 1961 at the age of 99 years and 5 months. He enjoyed a long and successful career in baseball: 18 seasons on professional teams, including 5 with the Cincinnati Red Stockings. He was one of the few players to have played in 4 of the 5 recognized major leagues: The National League, the short-lived Players’ League, the original American Association, and the American League.

worth “Dummy” Hoy (1862-1961) was the first deaf player to have a long career in the major leagues. He was born in 1862 in Houcktown, northern Ohio, graduated from Ohio School for the Deaf, began his professional career in 1886, played for several major-league teams from 1888 to 1902, and died in Cincinnati in 1961 at the age of 99 years and 5 months. He enjoyed a long and successful career in baseball: 18 seasons on professional teams, including 5 with the Cincinnati Red Stockings. He was one of the few players to have played in 4 of the 5 recognized major leagues: The National League, the short-lived Players’ League, the original American Association, and the American League.

Hoy was a small man, 5’4″ or 5’5″ tall, weighing 145-155 pounds, probably the shortest major-league outfielder in history. What he lacked in heft, he made up for in cunning and swiftness. He was a celebrated “flyhawk,” a great centerfielder, on a par with Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays, and Tris Speaker. During his rookie year in the majors (1888), Hoy led the National League with 82 stolen bases, a record that tops those of some of the most celebrated Hall of Famers. (Ty Cobb stole no bases during his rookie year, Babe Ruth 10.) His career total: 597 to 607 stolen bases (depending on which account you read).

Hoy had a respectable .288 (.292 according to some counts) lifetime batting average, and 2,054 hits. He once hit .357. He had 1,004 walks, and played in 1,798 major-league games. As baseball historian Nicholas Dawidoff has noted: “He was always among the league leaders in assists, totaling 318 in his 14 years, including an astounding 45 in 1900 . . . [on the] Chicago White Stockings”. Over the course of 137 games Hoy, who was then 38, had 337 putouts and a .977 fielding average to go along with his 45 assists. It was the only time an outfielder has ever led the majors in all three categories.”

An ill-fated fly ball batted by Hoy in 1894 was responsible for the league-wide ban on uniform breast pockets—a ban still in effect.

Hoy’s own proudest achievement was throwing out three baserunners at home plate in one game—an unprecedented and seldom-equaled feat.

There are numerous accounts of Hoy’s exploits, and many of these can be verified from contemporary newspaper accounts. One popular story from his Oshkosh days tells how Hoy chased and caught a fly ball while balancing on the shaft of a buggy parked inside the stadium. Some versions of the tale have Hoy leaping astride the horse to catch the ball!

Hoy was gentlemanly and polite, well-liked by his teammates, and never (or seldom) got thrown out of a game for misconduct—quite a feat in those unruly days! His honesty was legendary. During one game, in darkening dusk, the umpire called the batter out for catching a ball on the fly, which sparked a commotion. He asked Hoy, who was playing center field, if the ball had been caught on the fly or on the bounce. Hoy told him it had been caught “on the bounce.” The umpire called the batter safe. Hoy’s teammates were furious. Hoy was satisfied that he had told the truth.

Hoy taught his teammates how to communicate in sign language—very useful on the field. The fans loved him. When he made a spectacular play, fans stood in the bleachers and wildly waved their arms and hats—an early form of “Deaf applause.”

Most importantly, Hoy played a pioneering role in the creation of the hand signals still used today in baseball games throughout the world. When he began his professional career in Oshkosh, all umpires’ calls were shouted. While at bat, Hoy had to ask his coach if a ball or strike had been called. The opposing pitcher took advantage of Hoy’s distraction, quick-pitching him—sending out the next pitch before he was ready. (He batted only .219 during his first season.) Around 1887, according to this story, Hoy wrote out a request to the third-base coach, asking him to raise his left arm to indicate a ball, his right arm for a strike. Hoy could follow the hand signals after each pitch, and be ready for the next. And the umpires and other players found these signals so useful that they became standard practice—they’re still used everywhere. Hoy adapted the “out” and “safe” signals from ASL.

Thus, the intricate system of baseball hand signals—the umpire’s signals, manager’s call signals to batters, and the outfielders’ call signals now used in all levels of baseball and softball, can be traced to him and other early players like Edward Joseph “Dummy” Dundon and Luther Haden “Dummy” Taylor.